“A Tzadik in Peltz” is a Yiddish aphorism that describes a person who is (self) righteous but does not turn his or her righteousness towards others. Literally it means, “A righteous person in a (fur) coat.” As Rabbi Menachem of Kotkz explained: The Tzadik (in Peltz), warmly encased in protective fur, cannot appreciate the shivering of others.”

“A Tzadik in Peltz” is a Yiddish aphorism that describes a person who is (self) righteous but does not turn his or her righteousness towards others. Literally it means, “A righteous person in a (fur) coat.” As Rabbi Menachem of Kotkz explained: The Tzadik (in Peltz), warmly encased in protective fur, cannot appreciate the shivering of others.”

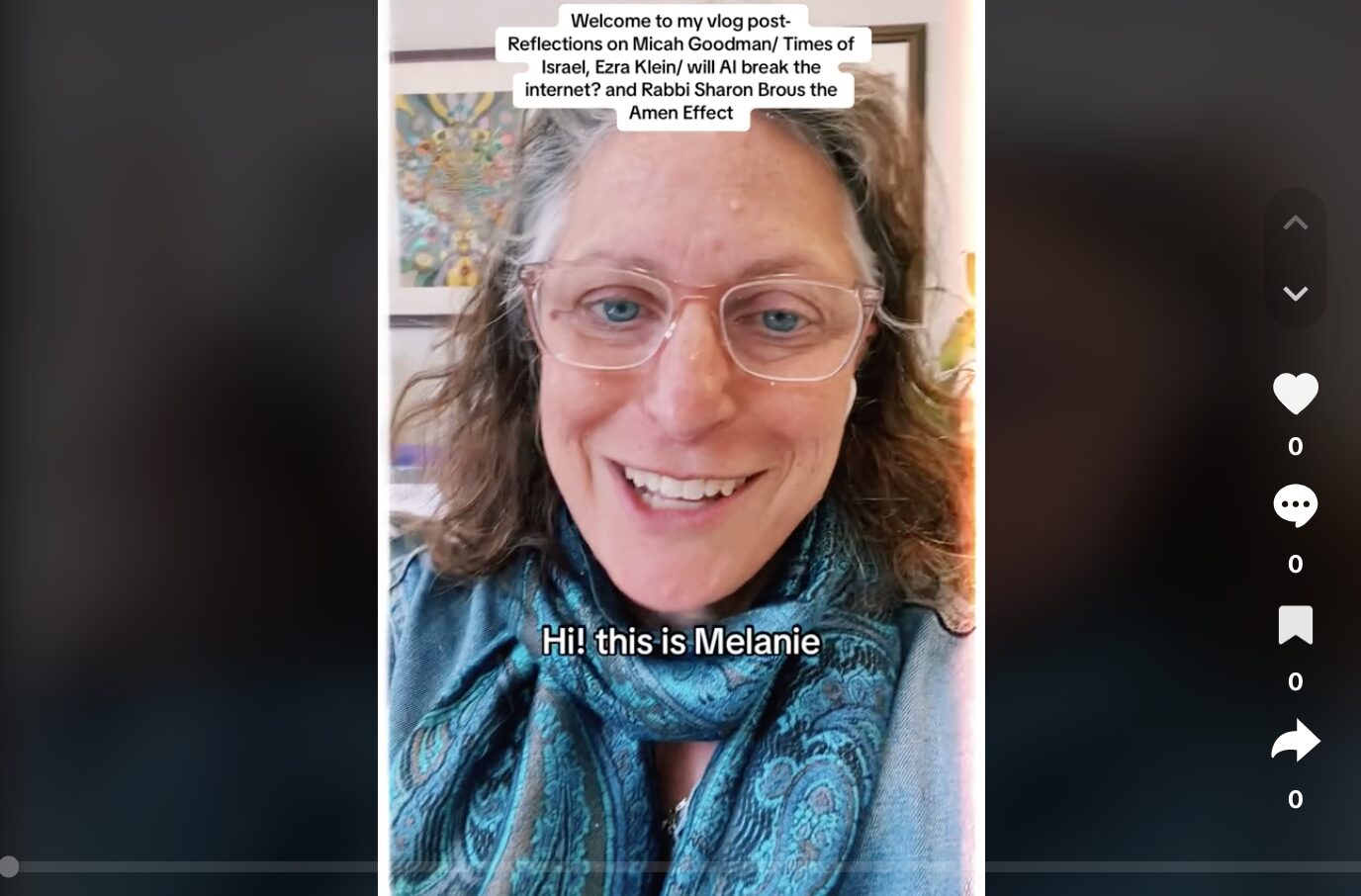

Rabbi Sheila Peltz Weinberg was our scholar-in-residence this week. She is an expert teacher of Mindfulness, a pioneer in bringing Mindful teaching to other Rabbis through the Institute of Jewish Spirituality she co-founded. For those who had the privilege of attending her talks, they found her to be a humble expert. We were not learning with her as much as we learning from her—from her own struggles being Mindful.

When hearing that her maiden name is Peltz the teaching came to mind. One of the first stories she read from her book Surprisingly Happy: An Atypical Religious Memoir is about her relationship with her mother. Many of us could (un)easily related to the theme; a mother insistent on her daughter needing something the daughter did not need or want. In her case it was a fur coat! Rabbi Sheila though did not have the energy or strength to say no to her mother, so she left the store with “this 25 pound suit of raccoon armor.” She wore it only rarely, mostly when she went to visit her Mother. The day came when she was ready to not be so afraid to hurt her mother’s feelings by returning it to her.

There are two types of spiritual teachers: Those who share themselves with you and those who share only their wisdom with you. Wisdom is indeed a great gift, but those spiritual teachers who do not share their own struggles are warmly encased in protective fur, not yet ready to reveal that they too are shivering along with you, struggling to settle the same issues we all deal with on a daily basis.

Rabbi Shiela Peltz (Weinberg) did more than just return the fur coat to her mother—she returned the favor by letting us in on her struggles. The expert on Mindfulness is the one that is mindful of how the shedding of our layers of clothing is a constant spiritual task.

david

2 Comments

Ilana · November 7, 2013 at 10:31 am

David,

You have such a superb way to convey ideas. When is the book coming? I can’t wait.

Anita Khaldy Kehmeier · November 4, 2018 at 9:20 pm

The Art of Now: Six Steps to Living in the Moment

We live in the age of distraction. Yet one of life’s sharpest paradoxes is that your brightest future hinges on your ability to pay attention to the present.

A friend was walking in the desert when he found the telephone to God. The setting was Burning Man, an electronic arts and music festival for which 50,000 people descend on Black Rock City, Nevada, for eight days of “radical self-expression”—dancing, socializing, meditating, and debauchery.

A phone booth in the middle of the desert with a sign that said “Talk to God” was a surreal sight even at Burning Man. The idea was that you picked up the phone, and God—or someone claiming to be God—would be at the other end to ease your pain.

So when God came on the line asking how he could help, my friend was ready. “How can I live more in the moment?” he asked. Too often, he felt, the beautiful moments of his life were drowned out by a cacophony of self-consciousness and anxiety. What could he do to hush the buzzing of his mind?

“Breathe,” replied a soothing male voice.

My friend flinched at the tired new-age mantra, then reminded himself to keep an open mind. When God talks, you listen.

“Whenever you feel anxious about your future or your past, just breathe,” continued God. “Try it with me a few times right now. Breathe in… breathe out.” And despite himself, my friend began to relax.

You Are Not Your Thoughts

Life unfolds in the present. But so often, we let the present slip away, allowing time to rush past unobserved and unseized, and squandering the precious seconds of our lives as we worry about the future and ruminate about what’s past. “We’re living in a world that contributes in a major way to mental fragmentation, disintegration, distraction, decoherence,” says Buddhist scholar B. Alan Wallace. We’re always doing something, and we allow little time to practice stillness and calm.

article continues after advertisement

When we’re at work, we fantasize about being on vacation; on vacation, we worry about the work piling up on our desks. We dwell on intrusive memories of the past or fret about what may or may not happen in the future. We don’t appreciate the living present because our “monkey minds,” as Buddhists call them, vault from thought to thought like monkeys swinging from tree to tree.

Most of us don’t undertake our thoughts in awareness. Rather, our thoughts control us. “Ordinary thoughts course through our mind like a deafening waterfall,” writes Jon Kabat-Zinn, the biomedical scientist who introduced meditation into mainstream medicine. In order to feel more in control of our minds and our lives, to find the sense of balance that eludes us, we need to step out of this current, to pause, and, as Kabat-Zinn puts it, to “rest in stillness—to stop doing and focus on just being.”

We need to live more in the moment. Living in the moment—also called mindfulness—is a state of active, open, intentional attention on the present. When you become mindful, you realize that you are not your thoughts; you become an observer of your thoughts from moment to moment without judging them. Mindfulness involves being with your thoughts as they are, neither grasping at them nor pushing them away. Instead of letting your life go by without living it, you awaken to experience.

Cultivating a nonjudgmental awareness of the present bestows a host of benefits. Mindfulness reduces stress, boosts immune functioning, reduces chronic pain, lowers blood pressure, and helps patients cope with cancer. By alleviating stress, spending a few minutes a day actively focusing on living in the moment reduces the risk of heart disease. Mindfulness may even slow the progression of HIV.

article continues after advertisement

Mindful people are happier, more exuberant, more empathetic, and more secure. They have higher self-esteem and are more accepting of their own weaknesses. Anchoring awareness in the here and now reduces the kinds of impulsivity and reactivity that underlie depression, binge eating, and attention problems. Mindful people can hear negative feedback without feeling threatened. They fight less with their romantic partners and are more accommodating and less defensive. As a result, mindful couples have more satisfying relationships.

Mindfulness is at the root of Buddhism, Taoism, and many Native-American traditions, not to mention yoga. It’s why Thoreau went to Walden Pond; it’s what Emerson and Whitman wrote about in their essays and poems.

“Everyone agrees it’s important to live in the moment, but the problem is how,” says Ellen Langer, a psychologist at Harvard and author of Mindfulness. “When people are not in the moment, they’re not there to know that they’re not there.” Overriding the distraction reflex and awakening to the present takes intentionality and practice.

Living in the moment involves a profound paradox: You can’t pursue it for its benefits. That’s because the expectation of reward launches a future-oriented mindset, which subverts the entire process. Instead, you just have to trust that the rewards will come. There are many paths to mindfulness—and at the core of each is a paradox. Ironically, letting go of what you want is the only way to get it. Here are a few tricks to help you along.

1: To improve your performance, stop thinking about it (unselfconsciousness).

article continues after advertisement

I’ve never felt comfortable on a dance floor. My movements feel awkward. I feel like people are judging me. I never know what to do with my arms. I want to let go, but I can’t, because I know I look ridiculous.

“Loosen up, no one’s watching you,” people always say. “Everyone’s too busy worrying about themselves.” So how come they always make fun of my dancing the next day?

The dance world has a term for people like me: “absolute beginner.” Which is why my dance teacher, Jessica Hayden, the owner of Shockra Studio in Manhattan, started at the beginning, sitting me down on a bench and having me tap my feet to the beat as Jay-Z thumped away in the background. We spent the rest of the class doing “isolations”—moving just our shoulders, ribs, or hips—to build “body awareness.”

But even more important than body awareness, Hayden said, was present-moment awareness. “Be right here right now!” she’d say. “Just let go and let yourself be in the moment.”

That’s the first paradox of living in the moment: Thinking too hard about what you’re doing actually makes you do worse. If you’re in a situation that makes you anxious—giving a speech, introducing yourself to a stranger, dancing—focusing on your anxiety tends to heighten it. “When I say, ‘be here with me now,’ I mean don’t zone out or get too in-your-head—instead, follow my energy, my movements,” says Hayden. “Focus less on what’s going on in your mind and more on what’s going on in the room, less on your mental chatter and more on yourself as part of something.” To be most myself, I needed to focus on things outside myself, like the music or the people around me.

Indeed, mindfulness blurs the line between self and other, explains Michael Kernis, a psychologist at the University of Georgia. “When people are mindful, they’re more likely to experience themselves as part of humanity, as part of a greater universe.” That’s why highly mindful people such as Buddhist monks talk about being “one with everything.”

By reducing self-consciousness, mindfulness allows you to witness the passing drama of feelings, social pressures, even of being esteemed or disparaged by others without taking their evaluations personally, explain Richard Ryan and K. W. Brown of the University of Rochester. When you focus on your immediate experience without attaching it to your self-esteem, unpleasant events like social rejection—or your so-called friends making fun of your dancing—seem less threatening.

Focusing on the present moment also forces you to stop overthinking. “Being present-minded takes away some of that self-evaluation and getting lost in your mind—and in the mind is where we make the evaluations that beat us up,” says Stephen Schueller, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania. Instead of getting stuck in your head and worrying, you can let yourself go.

2: To avoid worrying about the future, focus on the present (savoring).

In her memoir Eat, Pray, Love, Elizabeth Gilbert writes about a friend who, whenever she sees a beautiful place, exclaims in a near panic, “It’s so beautiful here! I want to come back here someday!” “It takes all my persuasive powers,” writes Gilbert, “to try to convince her that she is already here.”

Often, we’re so trapped in thoughts of the future or the past that we forget to experience, let alone enjoy, what’s happening right now. We sip coffee and think, “This is not as good as what I had last week.” We eat a cookie and think, “I hope I don’t run out of cookies.”

Instead, relish or luxuriate in whatever you’re doing at the present moment—what psychologists call savoring. “This could be while you’re eating a pastry, taking a shower, or basking in the sun. You could be savoring a success or savoring music,” explains Sonja Lyubomirsky, a psychologist at the University of California at Riverside and author of The How of Happiness. “Usually it involves your senses.”

When subjects in a study took a few minutes each day to actively savor something they usually hurried through—eating a meal, drinking a cup of tea, walking to the bus—they began experiencing more joy, happiness, and other positive emotions, and fewer depressive symptoms, Schueller found.

Why does living in the moment make people happier—not just at the moment they’re tasting molten chocolate pooling on their tongue, but lastingly? Because most negative thoughts concern the past or the future. As Mark Twain said, “I have known a great many troubles, but most of them never happened.” The hallmark of depression and anxiety is catastrophizing—worrying about something that hasn’t happened yet and might not happen at all. Worry, by its very nature, means thinking about the future—and if you hoist yourself into awareness of the present moment, worrying melts away.

The flip side of worrying is ruminating, thinking bleakly about events in the past. And again, if you press your focus into the now, rumination ceases. Savoring forces you into the present, so you can’t worry about things that aren’t there.

3: If you want a future with your significant other, inhabit the present (breathe).

Living consciously with alert interest has a powerful effect on interpersonal life. Mindfulness actually inoculates people against aggressive impulses, say Whitney Heppner and Michael Kernis of the University of Georgia. In a study they conducted, each subject was told that other subjects were forming a group—and taking a vote on whether she could join. Five minutes later, the experimenter announced the results—either the subject had gotten the least number of votes and been rejected or she’d been accepted. Beforehand, half the subjects had undergone a mindfulness exercise in which each slowly ate a raisin, savoring its taste and texture and focusing on each sensation.

Later, in what they thought was a separate experiment, subjects had the opportunity to deliver a painful blast of noise to another person. Among subjects who hadn’t eaten the raisin, those who were told they’d been rejected by the group became aggressive, inflicting long and painful sonic blasts without provocation. Stung by social rejection, they took it out on other people.

But among those who’d eaten the raisin first, it didn’t matter whether they’d been ostracized or embraced. Either way, they were serene and unwilling to inflict pain on others—exactly like those who were given word of social acceptance.

How does being in the moment make you less aggressive? “Mindfulness decreases ego involvement,” explains Kernis. “So people are less likely to link their self-esteem to events and more likely to take things at face value.” Mindfulness also makes people feel more connected to other people—that empathic feeling of being “at one with the universe.”

Mindfulness boosts your awareness of how you interpret and react to what’s happening in your mind. It increases the gap between emotional impulse and action, allowing you to do what Buddhists call recognizing the spark before the flame. Focusing on the present reboots your mind so you can respond thoughtfully rather than automatically. Instead of lashing out in anger, backing down in fear, or mindlessly indulging a passing craving, you get the opportunity to say to yourself, “This is the emotion I’m feeling. How should I respond?”

Mindfulness increases self-control; since you’re not getting thrown by threats to your self-esteem, you’re better able to regulate your behavior. That’s the other irony: Inhabiting your own mind more fully has a powerful effect on your interactions with others.

Of course, during a flare-up with your significant other it’s rarely practical to duck out and savor a raisin. But there’s a simple exercise you can do anywhere, anytime to induce mindfulness: Breathe. As it turns out, the advice my friend got in the desert was spot-on. There’s no better way to bring yourself into the present moment than to focus on your breathing. Because you’re placing your awareness on what’s happening right now, you propel yourself powerfully into the present moment. For many, focusing on the breath is the preferred method of orienting themselves to the now—not because the breath has some magical property, but because it’s always there with you.

4: To make the most of time, lose track of it (flow).

Perhaps the most complete way of living in the moment is the state of total absorption psychologists call flow. Flow occurs when you’re so engrossed in a task that you lose track of everything else around you. Flow embodies an apparent paradox: How can you be living in the moment if you’re not even aware of the moment? The depth of engagement absorbs you powerfully, keeping attention so focused that distractions cannot penetrate. You focus so intensely on what you’re doing that you’re unaware of the passage of time. Hours can pass without you noticing.

Flow is an elusive state. As with romance or sleep, you can’t just will yourself into it—all you can do is set the stage, creating the optimal conditions for it to occur.

The first requirement for flow is to set a goal that’s challenging but not unattainable—something you have to marshal your resources and stretch yourself to achieve. The task should be matched to your ability level—not so difficult that you’ll feel stressed, but not so easy that you’ll get bored. In flow, you’re firing on all cylinders to rise to a challenge.

To set the stage for flow, goals need to be clearly defined so that you always know your next step. “It could be playing the next bar in a scroll of music, or finding the next foothold if you’re a rock climber, or turning the page if you’re reading a good novel,” says Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the psychologist who first defined the concept of flow. “At the same time, you’re kind of anticipating.”

You also need to set up the task in such a way that you receive direct and immediate feedback; with your successes and failures apparent, you can seamlessly adjust your behavior. A climber on the mountain knows immediately if his foothold is secure; a pianist knows instantly when she’s played the wrong note.

As your attentional focus narrows, self-consciousness evaporates. You feel as if your awareness merges with the action you’re performing. You feel a sense of personal mastery over the situation, and the activity is so intrinsically rewarding that although the task is difficult, action feels effortless.

5: If something is bothering you, move toward it rather than away from it (acceptance).

We all have pain in our lives, whether it’s the ex we still long for, the jackhammer snarling across the street, or the sudden wave of anxiety when we get up to give a speech. If we let them, such irritants can distract us from the enjoyment of life. Paradoxically, the obvious response—focusing on the problem in order to combat and overcome it—often makes it worse, argues Stephen Hayes, a psychologist at the University of Nevada.

The mind’s natural tendency when faced with pain is to attempt to avoid it—by trying to resist unpleasant thoughts, feelings, and sensations. When we lose a love, for instance, we fight our feelings of heartbreak. As we get older, we work feverishly to recapture our youth. When we’re sitting in the dentist’s chair waiting for a painful root canal, we wish we were anywhere but there. But in many cases, negative feelings and situations can’t be avoided—and resisting them only magnifies the pain.

The problem is we have not just primary emotions but also secondary ones—emotions about other emotions. We get stressed out and then think, “I wish I weren’t so stressed out.” The primary emotion is stress over your workload. The secondary emotion is feeling, “I hate being stressed.”

It doesn’t have to be this way. The solution is acceptance—letting the emotion be there. That is, being open to the way things are in each moment without trying to manipulate or change the experience—without judging it, clinging to it, or pushing it away. The present moment can only be as it is. Trying to change it only frustrates and exhausts you. Acceptance relieves you of this needless extra suffering.

Suppose you’ve just broken up with your girlfriend or boyfriend; you’re heartbroken, overwhelmed by feelings of sadness and longing. You could try to fight these feelings, essentially saying, “I hate feeling this way; I need to make this feeling go away.” But by focusing on the pain—being sad about being sad—you only prolong the sadness. You do yourself a favor by accepting your feelings, saying instead, “I’ve just had a breakup. Feelings of loss are normal and natural. It’s OK for me to feel this way.”

Acceptance of an unpleasant state doesn’t mean you don’t have goals for the future. It just means you accept that certain things are beyond your control. The sadness, stress, pain, or anger is there whether you like it or not. Better to embrace the feeling as it is.

Nor does acceptance mean you have to like what’s happening. “Acceptance of the present moment has nothing to do with resignation,” writes Kabat-Zinn. “Acceptance doesn’t tell you what to do. What happens next, what you choose to do; that has to come out of your understanding of this moment.”

If you feel anxiety, for instance, you can accept the feeling, label it as anxiety—then direct your attention to something else instead. You watch your thoughts, perceptions, and emotions flit through your mind without getting involved. Thoughts are just thoughts. You don’t have to believe them and you don’t have to do what they say.

6: Know that you don’t know (engagement).

You’ve probably had the experience of driving along a highway only to suddenly realize you have no memory or awareness of the previous 15 minutes. Maybe you even missed your exit. You just zoned out; you were somewhere else, and it’s as if you’ve suddenly woken up at the wheel. Or maybe it happens when you’re reading a book: “I know I just read that page, but I have no idea what it said.”

These autopilot moments are what Harvard’s Ellen Langer calls mindlessness—times when you’re so lost in your thoughts that you aren’t aware of your present experience. As a result, life passes you by without registering on you. The best way to avoid such blackouts, Langer says, is to develop the habit of always noticing new things in whatever situation you’re in. That process creates engagement with the present moment and releases a cascade of other benefits. Noticing new things puts you emphatically in the here and now.

We become mindless, Langer explains, because once we think we know something, we stop paying attention to it. We go about our morning commute in a haze because we’ve trod the same route a hundred times before. But if we see the world with fresh eyes, we realize almost everything is different each time—the pattern of light on the buildings, the faces of the people, even the sensations and feelings we experience along the way. Noticing imbues each moment with a new, fresh quality. Some people have termed this “beginner’s mind.”

By acquiring the habit of noticing new things, says Langer, we recognize that the world is actually changing constantly. We really don’t know how the espresso is going to taste or how the commute will be—or at least, we’re not sure.

Orchestra musicians who are instructed to make their performance new in subtle ways not only enjoy themselves more but audiences actually prefer those performances. “When we’re there at the moment, making it new, it leaves an imprint in the music we play, the things we write, the art we create, in everything we do,” says Langer. “Once you recognize that you don’t know the things you’ve always taken for granted, you set out of the house quite differently. It becomes an adventure in noticing—and the more you notice, the more you see.” And the more excitement you feel.

Don’t Just Do Something, Sit There

Living a consistently mindful life takes effort. But mindfulness itself is easy. “People set the goal of being mindful for the next 20 minutes or the next two weeks, then they think mindfulness is difficult because they have the wrong yardstick,” says Jay Winner, a California-based family physician and author of Take the Stress out of Your Life. “The correct yardstick is just for this moment.”

Mindfulness is the only intentional, systematic activity that is not about trying to improve yourself or get anywhere else, explains Kabat-Zinn. It is simply a matter of realizing where you already are. A cartoon from The New Yorker sums it up: Two monks are sitting side by side, meditating. The younger one is giving the older one a quizzical look, to which the older one responds, “Nothing happens next. This is it.”

You can become mindful at any moment just by paying attention to your immediate experience. You can do it right now. What’s happening this instant? Think of yourself as an eternal witness, and just observe the moment. What do you see, hear, smell? It doesn’t matter how it feels—pleasant or unpleasant, good or bad—you roll with it because it’s what’s present; you’re not judging it. And if you notice your mind wandering, bring yourself back. Just say to yourself, “Now. Now. Now.”

Here’s the most fundamental paradox of all: Mindfulness isn’t a goal, because goals are about the future, but you do have to set the intention of paying attention to what’s happening at the present moment. As you read the words printed on this page, as your eyes distinguish the black squiggles on white paper, as you feel gravity anchoring you to the planet, wake up. Become aware of being alive. And breathe. As you draw your next breath, focus on the rise of your abdomen on the in-breath, the stream of heat through your nostrils on the out-breath. If you’re aware of that feeling right now, as you’re reading this, you’re living in the moment. Nothing happens next. It’s not a destination. This is it. You’re already there.