“Would she talk about what happened?” “No, never and if you can believe it, my uncle even less than that!” Growing up in Queens, NY most of my friends ‘parents were from Europe. They had come to the states after the war. Either one or both parents had numbers branded on their arms.

“Would she talk about what happened?” “No, never and if you can believe it, my uncle even less than that!” Growing up in Queens, NY most of my friends ‘parents were from Europe. They had come to the states after the war. Either one or both parents had numbers branded on their arms.

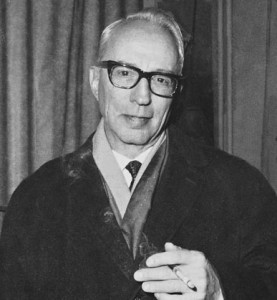

As a first year student studying for my doctorate in psychology I was introduced to Dr. Israel Zwerling, the chair of the Department of Psychiatry, who was collaborating with one of our professors on a study of children of Holocaust Survivors. It was through this project that what I had “learned” by osmosis was corroborated by scientific method.

In last week’s blog I introduced my sister’s best friend Mirel who came to Denver to connect with her family’s past—her great uncle was inexplicably buried here in Denver in the Temple Emanuel section of Fairmount Cemetery. I will circle back to that yet unfolding story. But the discussion with Mirel last night helped me understand why she had travelled 8,000 miles to find a grave of a man who died in 1919.

Mirel’s parents were both Holocaust survivors. Her father and his immediate family were hidden in a Slovakian forest for close to a year and cared for by a farmer and his family. Mirel’s mother’s family entered Auschwitz—her mother Alice and her uncle David were the only ones to survive. From my participation in the Children of Holocaust Survivor research Mirel’s story is both unique and typical. Although her mother would not talk about what happened she was an atypical survivor. If Mirel asked questions she would answer. Typical for the children of survivors: she rarely asked. It was clear that asking questions brought pain to her mother.

Family secrets come in many varieties. With loss, especially traumatic loss, a child’s sense of relationship with her parent’s how effective is propecia past becomes an arena of internal confusion and a need to know what happened (see Daniel Mendelsohn, Lost: Six of the Six Million). Mirel continues to spend a great deal of time and energy as a private investigator—her territory stretches from the Oregon coast to farmlands in Slovakia.

We gathered toward dusk yesterday, amidst the swarms of mosquitos, to honor Juilus Teitelbaum. It took us a while to find his headstone. It took even longer till the minyan (quorum) arrived for us to recite the Kaddish prayer. Julius though had been waiting almost a century for a connection with family. He was in no rush.

Circling back to the mystery, a simple question asked of google provided the answer. On Monday, Mirel found out that she had other relatives that lived in Denver—Julius’ uncle Adolph Berger had emigrated to Denver in 1882. According to records in the archives he had married twice, his first wife was Ida Levy. So I typed “Adolph Berger marries Ida Levy” and the first result was a very detailed biography about Julius David Berger, Adolph’s youngest son. http://www.pulpartists.com/BD.html

The Berger family moved from Denver to New York in 1922. In 1919, when his nephew died of injuries sustained as a sailor in the U.S. Navy during WWI, Adolph Berger was a member of Temple Emanuel. Julius had died in New York; his body was brought to Denver to be one of the first to be buried in the newly purchased Emanuel cemetery, far out on Quebec Street.

There are questions that are not comfortable for a child to ask. There is fear that the answers will cause pain. The stage then is set for asking questions, finding answers and finding “lost” relatives.

David

P.S. The author of the well-researched article written about Julius David Berger (pulpartists) in 2009: David Saunders.

1 Comment

Mirel · August 1, 2013 at 8:47 pm

That’s what happens when you shmooze with a psychologist 🙂

My uncle is going to love this. And BTW, I’ve already contacted Oregon…and found another uncle.

Thanks for everything!