When I was no more than 5 years old, I was pushing my younger brother in a carriage buggy, one of those more old fashioned types that the English call a pram. My memory of what happened is shrouded in the trauma that occurred—my brother’s tongue got caught (somehow) and deeply cut on the metal hinges securing the top cover. There was blood everywhere and my brother was rushed to the hospital for stiches. This memory is connected to a story line in my family of origin entitled “attempts on my brother’s life.” The next “attempt” occurred in a Florida pool, this one a very distinct memory of encouraging my younger brother, who was by then 6 or 7 to dive into the deep end of the pool. His two older sibs (our older sister and I) were there to catch him, but as he launched himself he got frightened and reached back for the side of the pool—his chin colliding with the concrete. Again, blood was gushing from my brother, again it was “my fault.”

When I was no more than 5 years old, I was pushing my younger brother in a carriage buggy, one of those more old fashioned types that the English call a pram. My memory of what happened is shrouded in the trauma that occurred—my brother’s tongue got caught (somehow) and deeply cut on the metal hinges securing the top cover. There was blood everywhere and my brother was rushed to the hospital for stiches. This memory is connected to a story line in my family of origin entitled “attempts on my brother’s life.” The next “attempt” occurred in a Florida pool, this one a very distinct memory of encouraging my younger brother, who was by then 6 or 7 to dive into the deep end of the pool. His two older sibs (our older sister and I) were there to catch him, but as he launched himself he got frightened and reached back for the side of the pool—his chin colliding with the concrete. Again, blood was gushing from my brother, again it was “my fault.”

A few years ago I was talking with my older sister, who revealed that not only was she present with me in the pool in Florida, she was by my side pushing the stroller. The stroller accident that I had believed was all my own doing—my first attempt on my brother’s life–had me think years later that it was more me, than my sister, who was “egging” my brother on to jump into the pool. My older sister, who had a different recollection of the stroller accident (she is two years older than me) added something profound as we talked, a simple sentence that altered my interpretation of that trauma. She asked me, “Did you ever wonder why we were given that responsibility of taking care of our brother at such a young age?” There is a family story line on this one as well, which, as I look back on it from my current vantage point, is a mixture of a more idyllic time in a sleepy, small town and a mother who often delegated care or her children to their older siblings (my older sister and I are the eldest of 6).

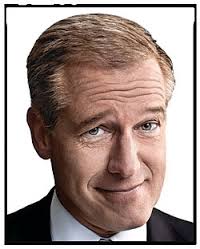

Chris Chabris and Daniel Simons, co-authors of The Invisible Gorilla: How our Intuitions Deceive Us, weigh in on the gaffe created by Brian Williams’ admission of misrepresenting a story from his Iraq war experience. Chabris and Simons conclude: “It’s unfortunate that so many people seem to have concluded that Brian Williams deliberately lied based solely on the fact that he recalled things that didn’t happen. Memory science shows that it’s nearly impossible to distinguish an honest mistake from a deliberate deception. A pattern of repeated exaggerations about different events, or documentary evidence from independent sources that Williams knew that what he was saying was untrue, would be more compelling evidence against the false memory explanation.”

Mr. Williams is now on leave for 6 months without pay from NBC. It is a time for him to reflect on the unfolding of his misrepresentations, be they conscious lies or unconscious distortions (I prefer that term to false) of memory. It also provides us time to reflect on our own memories, especially those associated with trauma and charged emotions, and to examine the memories themselves (click here to see the complete article by Chabirs and Simons) and how they have entered an interpretive story (or story line) of our life. It may not take 6 months but it has a potentially valuable pay-off; a new story for your life.

david

0 Comments